Showing posts with label sports and leisure. Show all posts

Showing posts with label sports and leisure. Show all posts

Tuesday, April 20, 2010

Thursday, March 01, 2007

Friday, December 22, 2006

Thursday, December 21, 2006

Wednesday, October 11, 2006

spectators' sport

Labels:

boston,

hair,

nightlife,

observation,

parties,

sports and leisure,

voyeurism

Saturday, September 09, 2006

Sunday, August 06, 2006

Wednesday, August 02, 2006

part of the process

Labels:

animal processing,

animals,

austin,

breakfast foods,

congress,

deer,

food,

signs,

sports and leisure,

texas

Friday, July 28, 2006

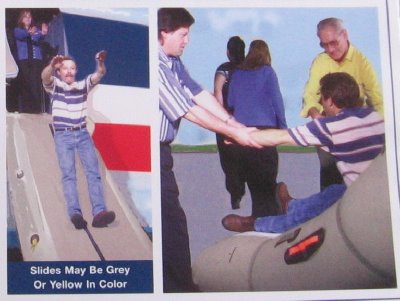

slides may be grey or yellow in color

Very few images need glossing, I find, but this is all about the poor execution of a simple idea. These two panels from the emergency instruction card I found on my United Airlines flight point up the very clear fact that not everyone should be allowed to use Photoshop. Foregrounds, backgrounds, and figures all seem to have been imported from different sources. How hard would it have been to photograph an actual person descending an emergency slide? Instead, the fellow on the left could easily be describing how high he'd like a load of cordwood stacked. Certainly he looks nothing like a real person sliding to safety out the door of a jetliner.

And what of the woman behind him? Disturbing. She appears to have shoved him out the door, her wooden expression showing plain distaste. Maybe she's just annoyed that he's ignored the common "women and children first" rule of evacuating distressed passenger vehicles.

In the right-hand panel, the passengers escape into a flat, barren backdrop. But what's that? Check out the woman in blue skulking away as the passenger from the slide is still being helped to his feet. It's the same woman who just shoved him out of the plane! She's everywhere!

Finally, let us please note that "slides may be grey or yellow in color." Do not be confused just because the inflatable rubber surface leading from the side of the plane to the ground is yellow. It's still a slide. Easy mistake to make, of course, if you're expecting it to be "grey." Entrust your life to it anyway. If it is orange, maroon, or aquamarine, you'll just have to take your chances.

Okay. If I've helped to save even one life here today, that will be enough. If not . . . well, that's fine too.

Labels:

airplanes,

boston,

chicago,

need for clarification,

signs,

sports and leisure,

warnings

Thursday, July 13, 2006

The Rambunctious Adventures of Jalasso Pei, part two

With the match suspended and the threat to her record averted, Jalasso returned to the peril of the moment: the wrath of her mother. A new wave of panic washed over her, and she dashed to the makeshift net to see if she could disentagle the knotted afghans and reposition the chairs from which they hung.

Miranda watched with vague interest while slowly packing her tennis gear.

“Need some help?” she asked over her shoulder after several moments. Jalasso had started in desperation to pull loose thick strands of yarn from the knit throws.

Jalasso glanced over at her. “Would you?”

“Ha!” Miranda laughed sarcastically. She stood and heaved her bulky saffron tennis bag over her shoulder. “You wish.” She headed for the door at the far end of Jalasso’s bedroom.

In frustration, Jalasso accidentally pulled loose several more strands of yarn from her mother’s expensive afghans. It seemed to her that at any minute the entire collection of knit items might unravel into one long, messy strand. She dropped the twisted mess as she watched Miranda striding toward the door. “Oh, yeah?” she shouted. “Well, next time we play, you’re going to wish something! That I’d stop kicking your skinny butt!”

She should have known from her long nine years of experience that just such a line would signal her mother’s entrance. It never failed that Mrs. Pei arrived always at the height of her daughter’s most outrageous exclamations. As the word “butt” left Jalasso’s lips, the heavy oak door flew open with a soft thud.

Jalasso leapt back a foot and covered her mouth involuntarily. Not because of the sudden terror her mother inspired, though she did. And not because it seemed very likely that she’d lose her court privileges for at least a month, though she probably would. But rather because the door to her room had just burst open with a thud, whereas it typically tended toward more of a crash. The difference between the sounds was accounted for by Miranda. She had just reached the door as Jalasso’s mother came in, and the door hit the girl square in the face.

Mrs. Pei’s reaction was less immediate. She had entered the room admonishing her daughter for her rambunctious, destructive behavior, for her rude treatment of her guest, and for her distinctly unladylike language. It took her a couple of seconds to process the details of the situation in Jalasso’s bedroom, and her tirade sputtered out as she took it all in. Jalasso stood still, eyes wide, hands over her mouth. Several of the antique throws looked in danger of being unraveled, and they were strapped to the delicately wroght chairs she’d hoped would downplay the sporty look of her daughter’s room. And finally, it seemed that little blonde girl Jalasso had a tennis rivalry with stood just inside the doorway. She was holding her nose and wailing in pain.

Mrs. Pei sputtered as she shifted her primary concern from confronting Jalasso about the broken window to kneeling down in front of the girl she’d evidently just hit in the face with the door.

Mrs. Pei held Miranda by the shoulders. “Oh, I’m so sorry, dear! I’m sorry! I didn’t know you were behind the door.”

Miranda continued to cry in high-pitched screams interspersed with long, low sobs. Mrs. Pei tried to pull the girl’s hands away from her face to see how badly she was hurt, but Miranda wouldn’t let her. She kept her whole face hidden, and her endless hours of tennis practice gave the little girl considerable upper body strength.

“Please, honey, let me see,” Mrs. Pei implored the girl. She disliked have to use a soft, mothering tone. Dealing with Jalasso’s unbridled energy and crafty willfulness had made such gentle measures so rare that they now felt false and foreign. But she had to cope with this situation as best she could. She didn’t think it would help to get stern or to overpower the girl.

Slowly, Miranda relaxed her arms, and Mrs. Pei drew her hands back. When she saw the girl’s face, she blanched. She tried not to react for fear of scaring her, but Miranda recognized the look of concern and uncertainty. She knew something was wrong.

Plus, it was hard not to notice the blood that dripped from her nose and now covered the bottom half of her face and both of her hands. Immediately, Miranda’s whimpering escalated into a series of high, anguished shrieks. Her hands flew back to cover her face and she sat down heavily on the floor, her tennis bag sliding off her shoulder and slumping to one side.

Mrs. Pei did her best to make soothing sounds, but Miranda seemed to be going into some mild form of shock. “Jalasso,” the woman whispered loudly, never taking her eyes off the injured child, “call down to Marble. Tell him your friend is hurt.”

Jalasso stood at the far side of the room, shifting her weight from one foot the other. She wanted to spring into action. She knew it was time. But for the time being, she felt incapable of moving. Things would just get worse from here, and she knew it. If only she could rewind things. Back to the match. To those last few returns. To that awful backhand of hers.

“Jalasso!” Mrs. Pei shouted in her best commanding voice.

The girls sprang into action, practically vaulting over her canopy bed toward her phone. She used the intercom function and heard the butler pick up as he always did in two rings, no more, no less.

“Marble!” she shrieked. “Mother’s calling for you. Miranda’s hurt!”

“Very good, Miss Jalasso,” Marble said in his unhurried, unflappable manner. “First aid or emergency?”

Monday, July 10, 2006

Wednesday, July 05, 2006

Saturday, July 01, 2006

The Rambunctious Adventures of Jalasso Pei, part one

Mishit

Jalasso had hoped the additional insulation and pricey soundproofing of her room would do the job. She needed it to muffle steady footfalls and shoe squeaks, to dampen the sharp smacks of tennis balls bouncing off the floor, and to smother her outraged cries as Miranda scored sneaky points.

And maybe it had worked. But even so, even the best soundproofing did nothing to hide a shattered bedroom window. Especially when the bright yellow tennis ball Jalasso had so terribly mishit sailed out that window, a shimmering trail of glass in its wake. Not when the spherical missile fell in bright noontime daylight four stories to the family estate’s vast green lawn. And not when the blasted thing then bounced, hopped, and rolled to a stop only a few yards from where her mother stood, discussing the details of Jalasso’s upcoming birthday lawn party with the groundskeeper.

As Jalasso stood looking out the windows and saw her mother’s beautiful pale moon of a face turn and look up at her angrily, she knew she would never be able to talk her way out of this one.

“So is that the match?” Miranda asked from over Jalasso’s shoulder as they watched Mrs. Pei walk stiffly toward the house.

Jalasso leapt down from the window seat and yanked one of the long, flowing curtains over the broken window. The wind outside gusted, pulling the curtain toward the jagged hole in the glass.

“What do you think, Miranda?” Jalasso asked testily, looking around the room at the obvious damage their game had caused.

“I think yeah,” Miranda said in a light tone. “But I’m just saying . . .”

Jalasso barely heard her. She had begun to run around her enormous bedroom, righting objects knocked over during the game, kicking stray tennis balls into her garage-sized walk-in closet, tucking the racquet she had been using under the mattress of her canopy bed. She did all this by force of habit, because she knew full well she could never get that window fixed before her mother made the long trek up to the fourth floor and down the long corridors toward the wing of the house that contained Jalasso’s bedroom. Besides, how would she ever have explained the ball? And all that glass outside? The makeshift net of antique afghan throws strung between two Chippendale chairs in the middle of the room?

Suddenly, she spun back toward Miranda, who still stood by the window, her racquet gripped lightly in her left hand. She glared. “You’re just saying what?” Jalasso asked suspiciously.

Miranda shrugged. “You’re down a set.”

Jalasso’s mouth fell open in astonishment. “What a cheap win!” she exclaimed. “That’s what it means to you when my mother’s about to come in here and revoke all my court privileges for the rest of the spring?”

Miranda tried to look hurt, but the expression was so unnatural for her that she looked instead like she was just recovering from a bad sneeze. “Like you wouldn’t! You’re still counting that game when I had an allergic reaction to that bee sting!”

For a moment, Jalasso forgot about the impending doom of Mrs. Pei. “That was totally fair,” she said. “Forfeiting for medical reasons.”

“My throat was going to close up!” Miranda yelled.

Jalasso threw her hands in the air. “So you made the right decision!”

Miranda grinned triumphantly. “So now it’s your turn,” she said. “Do we continue the game, or are you going to forfeit?”

Jalasso jumped up and down several times in frustration. She stomped her feet. “Why can’t we play it later?” she whined.

Miranda looked at her bare wrist as if she had a watch on it. “It’s match time now.”

Jalasso stopped suddenly and let her shoulders drop. She felt defeated, and she wanted just to fall down on the floor.

“Forfeit?” Miranda asked. She twirled her racquet in her hand.

Jalasso looked up at her sometime-friend and her small face broke into a grin. Her dark eyes glared up from under her choppy bangs. “Fine,” she said, “we’ll play. It’s still your serve.”

It was Miranda’s turn to look sincerely outraged. “What?” she asked. “We can’t play now! Your mom is coming up here to ground you for the rest of forever.”

Jalasso feigned an unconvincing look of innocence. “We can’t play?”

Miranda shook her head at Jalasso’s stupidity. “Of course not!”

Jalasso grinned wickedly and pumped her small fist. “Okay, then,” she said. “If we can’t play, then I don’t forfeit. Game postponed due to weather.”

“There’s nothing wrong with the weather,” Miranda protested.

Jalasso nodded. “Well, it’s about to get really bad in here. Stormy, even.”

Miranda tossed her head in irritation and stomped toward her tennis bag to gather her belongings. “Fine, Jalasso, the game’s postponed,” she said icily. “But I’m writing down the score. We’ll play again when you can go out, in like ten years.”

[next chapter]

Tuesday, May 02, 2006

Saturday, April 29, 2006

What I'm About to Do on My Summer Vacation

Vincent looked at the shiny green coupe in the driveway. Then he looked at the small mountain of luggage Pancakes had stacked in the driveway by the front door. He had yet to investigate the available space in the rear of the car, but even from this distance he could see that the entire interior of the vehicle would never hold all the bags Pancakes wanted to bring on their trip. They wouldn’t be leaving anytime soon.

“What exactly were you thinking when you rented this car?” Vincent asked.

Pancakes looked defiant. “I was thinking, basically, ‘go.’ You said to get a car, so I got a car.”

“And you also packed your bags. You were the one who knew how big the car was, and then you packed these enormous bags. I just don’t really get that,” Vincent said.

Pancakes turned to walk away. Since when did Vincent question her? This was unexpected and new. And unwelcome. That dumb girlfriend of his, Jalasso, had changed him somehow. She couldn’t believe those two hadn’t stayed broken up. “Vincent,” she said as she went back to the house, “you know what I don’t get? How your little girlfriend let you come on this trip in the first place. Isn’t she jealous?”

Vincent turned and followed her. “I don’t think so,” he said.

“Oh, you don’t? Well, what’d she say when you told her?”

“Nothing.”

“Yeah, right. Nothing?”

“Well, I didn’t tell her yet.”

Pancakes stopped and turned to face him. “Are you kidding? You didn’t tell her?” She was pleased by that, but she tried to sound appropriately outraged. “How could you not tell your girlfriend?”

Vincent shrugged. “I don’t have to,” he said. “We’re on hold for the summer.”

“On hold? What is that?”

Vincent shrugged again. “I don’t really know,” he said. “That’s what we agreed. She was going away for the whole summer, so we said we’d be on hold. I don’t have to check in with her on everything. She doesn’t check with me.”

Pancakes squinted at him. “This was your idea?” she asked.

“Not really.”

Their road trip together had been hastily arranged, and Pancakes hadn’t really done all that much planning other than securing a car and overpacking. Vincent was taking care of the details. She assumed he knew that. They hadn’t really discussed it in detail. She’d simply known that it was essential for her to get lost for a little while, and she especially needed to lose her boyfriend Brandon, who had grown a bit too serious about their undefined relationship. Apparently after a few months he felt the need to start asking her questions about her feelings and her intentions, and none of these questions were to her liking as she didn’t have ready answers for them. It was really, she thought, the wrong time to press her on anything. She didn’t know and she didn’t know and she didn’t know. All she knew for sure was that her college plans for the fall had been established, and for the moment she needed to prepare herself for the imminent onslaught of effort that would bring. A chain-smoking pseudo-boyfriend didn’t enter the picture. At least not in a good way.

One of the more irritating aspects of Brandon’s behavior was the increasing static he seemed to have with Vincent. It was funny at first. Pancakes liked the fact that, as she said to Pastina, “the boys are getting tough.” Given the temperaments of the two guys in question, it would never come to more than a battle of wits, but after a few months of that, Pancakes was tiring of the game. Vincent obviously had the upper hand, witswise, and that prompted Brandon to become a little meaner in his comments in order to hold up his end of the animosity. One moment in particular stood out to Pancakes as indicative of the degree to which things had devolved. In May, her long beloved cat Mourning Becomes Electra (she never tired of explaining that the cat’s name was not, in fact, “Morning,” as people tended to assume) had died. Pancakes had arranged a small funeral at her family home, and she had been astonished when, standing over the two-by-three foot grave, Brandon had intimated that Vincent might have had something to do with the cat’s demise.

“What are you, Charlie Chan?” Vincent had asked. “Are you going to explain the method, motive, and opportunity for my crime?” Brandon had been stymied for a proper reply, saying only, “Just so you know, I’ve got my eye on you.” Looking back now, Pancakes realized that was the beginning of the end for Brandon. She hated to admit that something like that was so important to her, but his inability to spar verbally turned her off. After all, Vincent wasn’t exactly a sarcastic knock-out artist.

A lengthy delay later, after which it was so late that they decided to eat lunch at Pancakes’s house rather than drive an hour down the road and stop somewhere far less inviting, the road trip finally got underway. “The only thing is,” Pancakes said as she settled into the passenger seat and leafed through the enormous cloth album of compact discs she’d brought, “we have to be back sometime in August so we can get ready for school.”

“That was kind of implied,” Vincent said. “Besides, Jalasso will be back at the end of August.”

“Who?” Pancakes asked innocently.

“Jalasso?”

“Your ex?”

“My on-hold,” Vincent corrected her.

Pancakes smiled. “We’ll see. We’re going to be out on the road for a long time together, Vincent. You may not want to go back to her after I’m done with you.”

Vincent looked a bit panicked and took a drink from his bottle of water. “I don’t know where that came from,” he said.

“Yeah, well, I don’t know why you’re not telling me something else, then,” Pancakes said. She selected a disc and slid it into the player. “If you’re in love with that girl, why did you let her go off all unattached? What are you doing out here with me, alone and unsupervised?”

“You wanted to go on a trip.”

“What did you want to do?”

“Get the hell out of there so I could stop thinking about how much I wanted Jalasso to be around.”

Pancakes sipped at a cup of watery iced coffee. “Now we’re getting somewhere.”

Vincent sighed and shook his head. “It’s pathetic, I know.”

“It’s not pathetic to be in love with her,” Pancakes said. She felt very strange making the statement. She didn’t really believe it, but at the same time she realized it was still true.

“But the ‘on-hold’ part. I don’t want us to be on hold. We can not-be-together, but that doesn’t mean that we have to suspend things officially.”

“I get it.”

“I mean, after the spring break thing.” Vincent didn't have to explain further. He and Jalasso had come close to the end then. She'd spent her break in Florida. Enough said.

“I know. I’m sorry.”

“Yeah, I’m sorry too.”

The two rode in silence for a while, letting themselves be distracted by the insistent pulse of the music Pancakes had selected and the blur of scenery sliding past them as Vincent drove. Finally Pancakes said, “Well, if it makes you feel any better, Brandon actually cried when I told him I was leaving.”

Vincent tried unsuccessfully to suppress a small smile. “Sadly, it does make me feel better. Not that he was a bad guy, but still …”

“Yes, I know. And for the record, I never for a second thought you were a cat murderer.”

“It was just his whole thing,” Vincent said. “And always with the cigarettes. God, I mean, after a while the casual way he smokes seems really self-conscious, you know? Didn’t you say he smoked in the bath tub?”

Pancakes made a face. “Don’t remind me. I can’t tell you how gross it is to be in the shower and realize there’s ash and tobacco all over the place. He used the soap dish as an ashtray, and he never cleaned it out.”

“So you stopped smoking?” Vincent asked.

“Well …” Pancakes looked out the window. “Okay, not totally. I’m working on it. I hope I’ll be done by the time we get back.”

Vincent’s eyes widened. He took his gaze off the road for a moment to give Pancakes a look of fearful astonishment. “Are you telling me that you’re going to go through withdrawals with me along for the ride? I thought we were friends.”

“We are,” she said. “That’s what I’m counting on in the hopes that you won’t end up killing me if I get too cranky.”

“You were waiting to tell me that until after we crossed state lines, weren’t you?”

“I didn’t think we’d hit on it so early. Why? Are you going to turn back?”

“I guess not,” Vincent said.

“Yeah, so here we are: two old friends out on the road, recently single—”

“One of us is single. The other’s on hold.”

“Two old friends, one recently single, one quote on hold unquote. And one of us is giving up smoking. What about you, Vincent? Are you giving up something?”

“At this point,” he said, “hope.”

“What exactly were you thinking when you rented this car?” Vincent asked.

Pancakes looked defiant. “I was thinking, basically, ‘go.’ You said to get a car, so I got a car.”

“And you also packed your bags. You were the one who knew how big the car was, and then you packed these enormous bags. I just don’t really get that,” Vincent said.

Pancakes turned to walk away. Since when did Vincent question her? This was unexpected and new. And unwelcome. That dumb girlfriend of his, Jalasso, had changed him somehow. She couldn’t believe those two hadn’t stayed broken up. “Vincent,” she said as she went back to the house, “you know what I don’t get? How your little girlfriend let you come on this trip in the first place. Isn’t she jealous?”

Vincent turned and followed her. “I don’t think so,” he said.

“Oh, you don’t? Well, what’d she say when you told her?”

“Nothing.”

“Yeah, right. Nothing?”

“Well, I didn’t tell her yet.”

Pancakes stopped and turned to face him. “Are you kidding? You didn’t tell her?” She was pleased by that, but she tried to sound appropriately outraged. “How could you not tell your girlfriend?”

Vincent shrugged. “I don’t have to,” he said. “We’re on hold for the summer.”

“On hold? What is that?”

Vincent shrugged again. “I don’t really know,” he said. “That’s what we agreed. She was going away for the whole summer, so we said we’d be on hold. I don’t have to check in with her on everything. She doesn’t check with me.”

Pancakes squinted at him. “This was your idea?” she asked.

“Not really.”

Their road trip together had been hastily arranged, and Pancakes hadn’t really done all that much planning other than securing a car and overpacking. Vincent was taking care of the details. She assumed he knew that. They hadn’t really discussed it in detail. She’d simply known that it was essential for her to get lost for a little while, and she especially needed to lose her boyfriend Brandon, who had grown a bit too serious about their undefined relationship. Apparently after a few months he felt the need to start asking her questions about her feelings and her intentions, and none of these questions were to her liking as she didn’t have ready answers for them. It was really, she thought, the wrong time to press her on anything. She didn’t know and she didn’t know and she didn’t know. All she knew for sure was that her college plans for the fall had been established, and for the moment she needed to prepare herself for the imminent onslaught of effort that would bring. A chain-smoking pseudo-boyfriend didn’t enter the picture. At least not in a good way.

One of the more irritating aspects of Brandon’s behavior was the increasing static he seemed to have with Vincent. It was funny at first. Pancakes liked the fact that, as she said to Pastina, “the boys are getting tough.” Given the temperaments of the two guys in question, it would never come to more than a battle of wits, but after a few months of that, Pancakes was tiring of the game. Vincent obviously had the upper hand, witswise, and that prompted Brandon to become a little meaner in his comments in order to hold up his end of the animosity. One moment in particular stood out to Pancakes as indicative of the degree to which things had devolved. In May, her long beloved cat Mourning Becomes Electra (she never tired of explaining that the cat’s name was not, in fact, “Morning,” as people tended to assume) had died. Pancakes had arranged a small funeral at her family home, and she had been astonished when, standing over the two-by-three foot grave, Brandon had intimated that Vincent might have had something to do with the cat’s demise.

“What are you, Charlie Chan?” Vincent had asked. “Are you going to explain the method, motive, and opportunity for my crime?” Brandon had been stymied for a proper reply, saying only, “Just so you know, I’ve got my eye on you.” Looking back now, Pancakes realized that was the beginning of the end for Brandon. She hated to admit that something like that was so important to her, but his inability to spar verbally turned her off. After all, Vincent wasn’t exactly a sarcastic knock-out artist.

A lengthy delay later, after which it was so late that they decided to eat lunch at Pancakes’s house rather than drive an hour down the road and stop somewhere far less inviting, the road trip finally got underway. “The only thing is,” Pancakes said as she settled into the passenger seat and leafed through the enormous cloth album of compact discs she’d brought, “we have to be back sometime in August so we can get ready for school.”

“That was kind of implied,” Vincent said. “Besides, Jalasso will be back at the end of August.”

“Who?” Pancakes asked innocently.

“Jalasso?”

“Your ex?”

“My on-hold,” Vincent corrected her.

Pancakes smiled. “We’ll see. We’re going to be out on the road for a long time together, Vincent. You may not want to go back to her after I’m done with you.”

Vincent looked a bit panicked and took a drink from his bottle of water. “I don’t know where that came from,” he said.

“Yeah, well, I don’t know why you’re not telling me something else, then,” Pancakes said. She selected a disc and slid it into the player. “If you’re in love with that girl, why did you let her go off all unattached? What are you doing out here with me, alone and unsupervised?”

“You wanted to go on a trip.”

“What did you want to do?”

“Get the hell out of there so I could stop thinking about how much I wanted Jalasso to be around.”

Pancakes sipped at a cup of watery iced coffee. “Now we’re getting somewhere.”

Vincent sighed and shook his head. “It’s pathetic, I know.”

“It’s not pathetic to be in love with her,” Pancakes said. She felt very strange making the statement. She didn’t really believe it, but at the same time she realized it was still true.

“But the ‘on-hold’ part. I don’t want us to be on hold. We can not-be-together, but that doesn’t mean that we have to suspend things officially.”

“I get it.”

“I mean, after the spring break thing.” Vincent didn't have to explain further. He and Jalasso had come close to the end then. She'd spent her break in Florida. Enough said.

“I know. I’m sorry.”

“Yeah, I’m sorry too.”

The two rode in silence for a while, letting themselves be distracted by the insistent pulse of the music Pancakes had selected and the blur of scenery sliding past them as Vincent drove. Finally Pancakes said, “Well, if it makes you feel any better, Brandon actually cried when I told him I was leaving.”

Vincent tried unsuccessfully to suppress a small smile. “Sadly, it does make me feel better. Not that he was a bad guy, but still …”

“Yes, I know. And for the record, I never for a second thought you were a cat murderer.”

“It was just his whole thing,” Vincent said. “And always with the cigarettes. God, I mean, after a while the casual way he smokes seems really self-conscious, you know? Didn’t you say he smoked in the bath tub?”

Pancakes made a face. “Don’t remind me. I can’t tell you how gross it is to be in the shower and realize there’s ash and tobacco all over the place. He used the soap dish as an ashtray, and he never cleaned it out.”

“So you stopped smoking?” Vincent asked.

“Well …” Pancakes looked out the window. “Okay, not totally. I’m working on it. I hope I’ll be done by the time we get back.”

Vincent’s eyes widened. He took his gaze off the road for a moment to give Pancakes a look of fearful astonishment. “Are you telling me that you’re going to go through withdrawals with me along for the ride? I thought we were friends.”

“We are,” she said. “That’s what I’m counting on in the hopes that you won’t end up killing me if I get too cranky.”

“You were waiting to tell me that until after we crossed state lines, weren’t you?”

“I didn’t think we’d hit on it so early. Why? Are you going to turn back?”

“I guess not,” Vincent said.

“Yeah, so here we are: two old friends out on the road, recently single—”

“One of us is single. The other’s on hold.”

“Two old friends, one recently single, one quote on hold unquote. And one of us is giving up smoking. What about you, Vincent? Are you giving up something?”

“At this point,” he said, “hope.”

Monday, February 20, 2006

Tuesday, November 01, 2005

He’s Going the Distance!

He balanced between the parallel bars, holding himself up with minimal effort. His arms were locked, his weight pulling straight down. As long as he could hold the position, he could keep his feet clear of the ground. The moment he lost his poise, he’d have to drop. He’d been hanging there for eight minutes already, and some kids were starting to notice.

“He’s hypnotized!” Rudy shouted to the thirty-eight other kids playing on the blacktop beside the gym. “Bill’s hypnotized. He’s never coming down off the bars!”

Rudy always had to grab the attention. Here he was, holding himself in a perfectly balanced position for eight minutes, and Rudy had to be the one to blab about it. Rudy was always like that. Like when they played dodge ball. Rudy wasn’t even the best thrower. Not even tenth. But he shouted and made fun and acted like he was so great. Lucky for him he was great at least at dodging, because people aimed for his head sometimes.

Kids started to gather by the sets of steel monkey bars where Bill held himself suspended. His body hung between two of the handlebars, his hands wrapped halfway around each of the longer parallel support bars. He looked straight ahead, down along the south wall of the gymnasium toward the other playground, the one where the little kids in first and second grade played. Nobody ever went over there except after school hours. It was the enemy camp.

But Bill could see the kids gathering around without looking directly at them. He could see them out of the corner of his eye, and first there were just a couple of them, but then there were more and more. They kept coming until almost no one was on the other side of the blacktop anymore. A lot of the balls had stopped bouncing. Virginia and Betsy were still twirling their jump rope, but none of the other girls wanted to gain admittance to their inner circle for a change. Soon enough those two would return to power as the girls who set the standard for fun during after-lunch recess, but not at the moment. At the moment Bill was suspending himself into the grade-school history books. People were saying that he’d been hanging there now for nine minutes!

Tyler and two other kids, a boy and a girl, climbed up on the monkey bars near him. Tyler climbed up to his level and lowered himself into a position similar to Bill’s. He hung there in front of Bill, looking right into his face.

“What’re you doing?” Tyler asked.

“Testing my will,” Bill said.

The two other kids looked at each other. “What?” the girl said. She looked at the boy, then at Tyler. “What is he talking about?”

“What are you talking about?” Tyler asked. “It’s a test?”

“I’m testing myself,” Bill explained. “To see how far I can go.”

Tyler and the girl laughed. “You’re not going very far right now!” Tyler said. The other boy looked at Tyler and tried to laugh because others were laughing.

Bill felt his arms burning a little, but he still wasn’t exerting much force. He just kept himself centered, and he felt fine like that. He could see that Tyler had done it wrong. He wasn’t positioned right. He already kept shifting his weight from one arm to the other.

“That’s okay,” Bill said at last. He didn’t know what they wanted from him. He couldn’t help but look at Tyler from where he was, but he tried to look past him a little.

Tyler rolled his eyes and wiggled his head. “You’re crazy!” he shouted, and dropped to the ground. The other two kids with him laughed like he’d said the funniest thing in the world. They climbed down, and all three of them stepped back from the monkey bars to join the rest of the class.

Bill’s elbows felt wobbly. He tried to steady himself by looking out across the ball field on the school yard. He looked at Myrtle Street beyond that and watched a blue car drive by and out of sight. If he didn’t think about his arms very much, he kind of forgot about them. What if he stayed up on the bars even past recess? Would they make him go inside? What if he was going to break a record or something? He hoped they’d check first before they made him stop.

“He’s hypnotized!” Rudy shouted to the thirty-eight other kids playing on the blacktop beside the gym. “Bill’s hypnotized. He’s never coming down off the bars!”

Rudy always had to grab the attention. Here he was, holding himself in a perfectly balanced position for eight minutes, and Rudy had to be the one to blab about it. Rudy was always like that. Like when they played dodge ball. Rudy wasn’t even the best thrower. Not even tenth. But he shouted and made fun and acted like he was so great. Lucky for him he was great at least at dodging, because people aimed for his head sometimes.

Kids started to gather by the sets of steel monkey bars where Bill held himself suspended. His body hung between two of the handlebars, his hands wrapped halfway around each of the longer parallel support bars. He looked straight ahead, down along the south wall of the gymnasium toward the other playground, the one where the little kids in first and second grade played. Nobody ever went over there except after school hours. It was the enemy camp.

But Bill could see the kids gathering around without looking directly at them. He could see them out of the corner of his eye, and first there were just a couple of them, but then there were more and more. They kept coming until almost no one was on the other side of the blacktop anymore. A lot of the balls had stopped bouncing. Virginia and Betsy were still twirling their jump rope, but none of the other girls wanted to gain admittance to their inner circle for a change. Soon enough those two would return to power as the girls who set the standard for fun during after-lunch recess, but not at the moment. At the moment Bill was suspending himself into the grade-school history books. People were saying that he’d been hanging there now for nine minutes!

Tyler and two other kids, a boy and a girl, climbed up on the monkey bars near him. Tyler climbed up to his level and lowered himself into a position similar to Bill’s. He hung there in front of Bill, looking right into his face.

“What’re you doing?” Tyler asked.

“Testing my will,” Bill said.

The two other kids looked at each other. “What?” the girl said. She looked at the boy, then at Tyler. “What is he talking about?”

“What are you talking about?” Tyler asked. “It’s a test?”

“I’m testing myself,” Bill explained. “To see how far I can go.”

Tyler and the girl laughed. “You’re not going very far right now!” Tyler said. The other boy looked at Tyler and tried to laugh because others were laughing.

Bill felt his arms burning a little, but he still wasn’t exerting much force. He just kept himself centered, and he felt fine like that. He could see that Tyler had done it wrong. He wasn’t positioned right. He already kept shifting his weight from one arm to the other.

“That’s okay,” Bill said at last. He didn’t know what they wanted from him. He couldn’t help but look at Tyler from where he was, but he tried to look past him a little.

Tyler rolled his eyes and wiggled his head. “You’re crazy!” he shouted, and dropped to the ground. The other two kids with him laughed like he’d said the funniest thing in the world. They climbed down, and all three of them stepped back from the monkey bars to join the rest of the class.

Bill’s elbows felt wobbly. He tried to steady himself by looking out across the ball field on the school yard. He looked at Myrtle Street beyond that and watched a blue car drive by and out of sight. If he didn’t think about his arms very much, he kind of forgot about them. What if he stayed up on the bars even past recess? Would they make him go inside? What if he was going to break a record or something? He hoped they’d check first before they made him stop.

Saturday, July 30, 2005

jalasso pei, part-time potential junior tennis champ (III)

[part two]

Part Three: The Tennis Bag . . .

“Okay, I’m not looking!” Jalasso announced to Tommy. She had her face turned toward the wall, her eyes closed, and both hands in front of her face for good measure. She really wanted to look like she wasn’t looking.

“Do you promise this time?” he asked. The last two times, she had been peeking.

“I’m not supposed to know where my racquet that needs to be restrung really is,” she explained for the fourth time. “So I can’t see where you put it.”

“I know,” Tommy said for the third time. “But you keep looking!”

“Bad habits,” Jalasso said. “But I have them under control now. Go.”

She heard Tommy rustling the heavy black and yellow tennis bag she’d given him. Obviously, she intended him to carry the lamp away with him, but she thought she could provide herself some protection from accidentally giving herself away by not seeing the crime. She tried not to imagine exactly how the lamp might be slipped into one of the side pouches meant to hold up to four rackets on each side. She tried not to wonder if the zipping sound she heard might be Tommy’s putting the cosmetics bag of glass in the front pouch intended for clusters of loose practice balls. And she tried even harder not to turn her head and look at how he was packing the bag once it occurred to her that he might put a couple of racquets in with it, and those might get scratched by that stupid Tiffany lamp. But she couldn’t look! Otherwise, she might end up blabbing if she knew where the lamp had gone. She wouldn’t mean to, but sometimes the words came out of her mouth before she could make them stop.

She heard someone clear her throat at the far end of the room. Jalasso’s mother stood in the doorway of her daughter’s bedroom. She frowned, eyes narrowed, hands on her hips. “Where do you think you’re going, young lady?” she asked.

Jalasso whirled and stared up at her mother in surprise. She glanced over and saw that Tommy had gotten the lamp safely packed away, but she felt her heart slamming against her chest all the same. She wasn’t safe yet. Her meeting with Johann Bjornbornssen still might be lost!

“What?” Jalasso asked, almost shouting in her nervousness.

“Excuse me?” her mother asked. “Is that any way to talk to you mother?” She glanced at Tommy, who stood nearby, looking at her with his usual mix of fear and awe. Mrs. Pei, it was widely agreed, was not only the prettiest mother out of all the mothers they knew. She was the prettiest anyone out of all the anyones they knew. But she was direct and stern and proper in a way that insured she could take issue with anyone at any time, if there seemed some advantage in it. “Hello, Tommy,” she said. “I’m sorry to barge in here like this, but it’s a full-time job keeping up with Jalasso’s comings and going.”

Tommy smiled at the recognition from Mrs. Pei, although it was nothing new. He’d been visiting the Pei house for a couple of years, ever since he and Jalasso met at a local tennis clinic and they found they belonged to the same country club. He nodded and smiled. “Hello, Mrs. Pei. Jalasso and I were going to play for a little while.”

Mrs. Pei cocked an eyebrow in her daughter’s direction. “Oh, is that where you were headed, dear?” she asked.

Jalasso smiled weakly and nodded. “Yes, ma’am.”

For a moment, Jalasso was certain her mother’s eyes were drawn to the spot in the room where the Tiffany lamp had stood, but then she continued. “Do we not ask permission in this house anymore? Your father is setting a bad example with all his travels, but this is a home, not a hotel. I don’t think tennis was on your schedule for this afternoon.”

Her mother was angry about the household schedule. She tried not to look as relieved as she felt, but knew that meant she looked plenty relieved already. “I’m sorry, Mother,” she said, regaining her composure. “It wasn’t a for-sure thing. Tommy didn’t know if he’d be able to come, so I forgot to add it.”

“Well, that’s not very good planning, Jalasso. We have to have a schedule, or nothing would ever get done around here. So apologize to Tommy for your mistake, but I’m afraid you have a tea at four. You don’t have time to visit the courts right now,” her mother said. She waited for the outburst that was sure to follow and prepared to threaten the cancellation of tennis camp again. It was one of her better tools for getting Jalasso’s compliance, but of course she would lose that power if she ever exercised it. Not to mention that two weeks free of her bounding, explosive little girl beckoned to her like a distant dream.

Jalasso surprised her mother by nodding once decisively, the way she sometimes did after making a convincing backhand, and turning to her friend. “I’m sorry, Tommy. I forgot to add our game to the schedule. I can’t go play with you today. Please forgive me.”

“Sure, that’s fine,” Tommy said. He didn’t move.

“We’ll have you over another time, Tommy. Maybe you can come for a morning game next weekend and stay for lunch. We’ll check the appointment book and set something up with you parents,” Mrs. Pei said.

“Great. Thank you,” Tommy said. He still stood awkwardly next to the oversized tennis bag at his feet.

“But right now I need Jalasso to figure out what she’s going to wear to the tea party.”

Jalasso suddenly realized how guilty she and Tommy both looked, and she rushed to Tommy’s side and shook hands with him awkwardly. “So I’ll see you soon, Tommy,” she said. “And we’ll play tennis!”

A look of understanding flashed across Tommy’s face and he leaned down to grab the large tennis bag and sling it over shoulder. “Yes, tennis is good,” he said. “I mean, that’ll be good. Playing tennis.”

“Hold on, Tommy,” Mrs. Pei said, and both children froze. “I’ll have someone take that bag down for you. It looks awfully heavy.”

“No!” Jalasso said, and her mother gave her a wide-eyed look as a reprimand. “I mean, that would be nice, but …”

“It’s very nice of you, Mrs. Pei,” Tommy said, trying to pick up the bag as casually as if it didn’t have a ruined antique lamp in it. “But you know how tennis players are. Always building up our muscles.” He hoped he didn’t sound like he was flirting with Jalasso’s mother. Tommy didn’t really know much about flirting, but he was pretty sure that’s what he had been doing.

Mrs. Pei looked unsure, but she stepped out of the doorway. “Yes, I do know how you tennis players are,” she said. She watched as the boy lugged the bulky bag out the door and down the hallway toward the central house. He was a good kid, she thought, and strangely loyal to Jalasso, despite the way she bossed him around. She could only assume that’s who had convinced him to attach the glittery unicorn sticker to the outside of his tennis bag.

Part Three: The Tennis Bag . . .

“Okay, I’m not looking!” Jalasso announced to Tommy. She had her face turned toward the wall, her eyes closed, and both hands in front of her face for good measure. She really wanted to look like she wasn’t looking.

“Do you promise this time?” he asked. The last two times, she had been peeking.

“I’m not supposed to know where my racquet that needs to be restrung really is,” she explained for the fourth time. “So I can’t see where you put it.”

“I know,” Tommy said for the third time. “But you keep looking!”

“Bad habits,” Jalasso said. “But I have them under control now. Go.”

She heard Tommy rustling the heavy black and yellow tennis bag she’d given him. Obviously, she intended him to carry the lamp away with him, but she thought she could provide herself some protection from accidentally giving herself away by not seeing the crime. She tried not to imagine exactly how the lamp might be slipped into one of the side pouches meant to hold up to four rackets on each side. She tried not to wonder if the zipping sound she heard might be Tommy’s putting the cosmetics bag of glass in the front pouch intended for clusters of loose practice balls. And she tried even harder not to turn her head and look at how he was packing the bag once it occurred to her that he might put a couple of racquets in with it, and those might get scratched by that stupid Tiffany lamp. But she couldn’t look! Otherwise, she might end up blabbing if she knew where the lamp had gone. She wouldn’t mean to, but sometimes the words came out of her mouth before she could make them stop.

She heard someone clear her throat at the far end of the room. Jalasso’s mother stood in the doorway of her daughter’s bedroom. She frowned, eyes narrowed, hands on her hips. “Where do you think you’re going, young lady?” she asked.

Jalasso whirled and stared up at her mother in surprise. She glanced over and saw that Tommy had gotten the lamp safely packed away, but she felt her heart slamming against her chest all the same. She wasn’t safe yet. Her meeting with Johann Bjornbornssen still might be lost!

“What?” Jalasso asked, almost shouting in her nervousness.

“Excuse me?” her mother asked. “Is that any way to talk to you mother?” She glanced at Tommy, who stood nearby, looking at her with his usual mix of fear and awe. Mrs. Pei, it was widely agreed, was not only the prettiest mother out of all the mothers they knew. She was the prettiest anyone out of all the anyones they knew. But she was direct and stern and proper in a way that insured she could take issue with anyone at any time, if there seemed some advantage in it. “Hello, Tommy,” she said. “I’m sorry to barge in here like this, but it’s a full-time job keeping up with Jalasso’s comings and going.”

Tommy smiled at the recognition from Mrs. Pei, although it was nothing new. He’d been visiting the Pei house for a couple of years, ever since he and Jalasso met at a local tennis clinic and they found they belonged to the same country club. He nodded and smiled. “Hello, Mrs. Pei. Jalasso and I were going to play for a little while.”

Mrs. Pei cocked an eyebrow in her daughter’s direction. “Oh, is that where you were headed, dear?” she asked.

Jalasso smiled weakly and nodded. “Yes, ma’am.”

For a moment, Jalasso was certain her mother’s eyes were drawn to the spot in the room where the Tiffany lamp had stood, but then she continued. “Do we not ask permission in this house anymore? Your father is setting a bad example with all his travels, but this is a home, not a hotel. I don’t think tennis was on your schedule for this afternoon.”

Her mother was angry about the household schedule. She tried not to look as relieved as she felt, but knew that meant she looked plenty relieved already. “I’m sorry, Mother,” she said, regaining her composure. “It wasn’t a for-sure thing. Tommy didn’t know if he’d be able to come, so I forgot to add it.”

“Well, that’s not very good planning, Jalasso. We have to have a schedule, or nothing would ever get done around here. So apologize to Tommy for your mistake, but I’m afraid you have a tea at four. You don’t have time to visit the courts right now,” her mother said. She waited for the outburst that was sure to follow and prepared to threaten the cancellation of tennis camp again. It was one of her better tools for getting Jalasso’s compliance, but of course she would lose that power if she ever exercised it. Not to mention that two weeks free of her bounding, explosive little girl beckoned to her like a distant dream.

Jalasso surprised her mother by nodding once decisively, the way she sometimes did after making a convincing backhand, and turning to her friend. “I’m sorry, Tommy. I forgot to add our game to the schedule. I can’t go play with you today. Please forgive me.”

“Sure, that’s fine,” Tommy said. He didn’t move.

“We’ll have you over another time, Tommy. Maybe you can come for a morning game next weekend and stay for lunch. We’ll check the appointment book and set something up with you parents,” Mrs. Pei said.

“Great. Thank you,” Tommy said. He still stood awkwardly next to the oversized tennis bag at his feet.

“But right now I need Jalasso to figure out what she’s going to wear to the tea party.”

Jalasso suddenly realized how guilty she and Tommy both looked, and she rushed to Tommy’s side and shook hands with him awkwardly. “So I’ll see you soon, Tommy,” she said. “And we’ll play tennis!”

A look of understanding flashed across Tommy’s face and he leaned down to grab the large tennis bag and sling it over shoulder. “Yes, tennis is good,” he said. “I mean, that’ll be good. Playing tennis.”

“Hold on, Tommy,” Mrs. Pei said, and both children froze. “I’ll have someone take that bag down for you. It looks awfully heavy.”

“No!” Jalasso said, and her mother gave her a wide-eyed look as a reprimand. “I mean, that would be nice, but …”

“It’s very nice of you, Mrs. Pei,” Tommy said, trying to pick up the bag as casually as if it didn’t have a ruined antique lamp in it. “But you know how tennis players are. Always building up our muscles.” He hoped he didn’t sound like he was flirting with Jalasso’s mother. Tommy didn’t really know much about flirting, but he was pretty sure that’s what he had been doing.

Mrs. Pei looked unsure, but she stepped out of the doorway. “Yes, I do know how you tennis players are,” she said. She watched as the boy lugged the bulky bag out the door and down the hallway toward the central house. He was a good kid, she thought, and strangely loyal to Jalasso, despite the way she bossed him around. She could only assume that’s who had convinced him to attach the glittery unicorn sticker to the outside of his tennis bag.

Tuesday, July 26, 2005

jalasso pei, part-time potential junior tennis champ (II)

[part one]

Part Two: The Racquet That Needs To Be Restrung

Jalasso couldn’t believe how obvious Tommy was when he came to sneak away with the lamp. She wanted him to do it right, and she had half a mind not to restore his name to the birthday party list because of his poor performance. It was only the effectiveness of the job that convinced her not to be too hasty. She could cut him from the list for some other trifle, but she’d never bribe another favor out of him if she went back on their deal. She’d just wait another week or so, then find something that he said so offensive that she’d have no choice but to drop him from the invitation list.

She had dumped the contents of her wastebasket into a cosmetics bag to keep the maids from finding the broken glass. Jalasso meant to get a trash bag, but she couldn’t find any and she didn’t want to raise suspicion by asking. Then she thought she might find a shopping bag, but those were all gone. Groceries were almost always brought to the house by delivery, so she couldn’t even find a simple brown bag. At least the cosmetics bag was just a giveaway item her mother got with some boutique purchase. Plus, it zipped, which kept it from spilling.

The lamp itself was a lot harder to figure out. She needed to hide both the lamp’s base and the tangle of metalwork that had once helped define the shape of the stained-glass lampshade. Jalasso experimented with the latticework of soft metal that had made up the shade, and she found she could bend it very easily. But there were still a lot of glass fragments stuck to it, so she worried that she might cut herself and then the cut would get infected and then she wouldn’t be able to hold her racquet right and something like that could very well cost you a match. Better not to risk it. And, really, that was mostly Tommy’s job, getting rid of the lamp. When he got there, he could bend the metalwork in order to make it fit.

She’d told Tommy to bring something to put the lamp base and shade in, because she was stumped. The base would stick out of most bags, and even if Tommy could mash it down, the shade was going to have a weird shape that would be hard to hide. What if she just threw them both out the window and Tommy maybe stood outside and caught them? But her room was four stories up. She’d seen Tommy try to return her own forehand, and she knew he wasn’t really that coordinated. Besides, somebody might see. But Tommy said he had an idea.

When the butler, Marble, announced Tommy at Jalasso’s bedroom door, he mentioned that young Mr. Penchant had arrived for their tennis date. Jalasso tried not to react, but she knew that if she realized she should try not to react, she probably already had reacted with the kind of annoyed look of surprise she always displayed when she heard something she hadn’t expected or didn’t like. But Marble didn’t care as long as he believed Jalasso’s current mischief wasn’t dangerous. Plus, Jalasso had to admit that nine times out of ten, that’s the reason any of her peers came to her room.

“But you didn’t even bring a racquet!” Jalasso complained once they were alone in her room. “That’s not believable. Tommy, please don’t get me in trouble. I’m serious.” Ever since Tommy agreed to come help her with the lamp, she’d been pacing her room, spinning her racquet in her hands, and nervously keeping balls aloft with gentle taps. She kept imagining her mother finding out about the lamp. She could almost hear the sound of her mother’s voice telling the tennis camp that, fine, they could keep her deposit. But no way was Jalasso Pei making an appearance that year at their facilities. She could see all the other girls lined up during the morning clinics, smiling and flirting with Johann Bjornbornssen. And stupid Amy with her stupid blonde pigtails grinning at him with her big stupid mouth and fat, fat lips. It had started to make Jalasso sick with anticipation.

“No one noticed,” Tommy said. “Besides, that’s how we’re taking everything out. In one of your tennis bags.”

Jalasso stopped for a moment as she took hold of the information. She could have done the same thing herself! The lamp was exactly the right size for one of her big shoulder bags. And if she bent it right, the shade would flatten out to be about the size of a racquet head. Of course, if one of the staff insisted as usual that they had to take the heavy items, then the lamp might have been discovered. They’d let Tommy take his own bag, however. Not to mention the fact that she wanted to avoid that cut to the hand that would threaten her game. That was a risk she preferred Tommy take. Still, one thing bothered Jalasso.

“So you’re just taking one of my bags?” she asked. “Do I get it back?”

Tommy frowned at her in disbelief. “Jalasso, you have about twenty tennis bags at least.”

She threw out her hands. Some people just didn’t get anything. “They’re all different,” she explained. “Different sizes and styles and pockets and stuff. And I have five different ones from five different years I’ve been to the Open. So those are mainly just for my collection.”

Tommy rolled his eyes as dramatically as a silent movie star. He shook his head. “Fine,” he said. “I’ll bring your bag back. Whatever one you can live without for a couple of days. Next time I come play you, I’ll bring it back.”

Jalasso shook her head. “And, what, leave your racquet?”

“I can borrow one of yours.”

She flinched as if someone had tried to strike her. “What? Be serious.”

Tommy made a noise of frustration. “Fine! I’ll leave mine. Or I’ll bring one with a head cover with a strap and stick it inside the bag. We’ll figure it out. Can we just get your busted lamp and go?”

Jalasso made a shushing motion at Tommy, although almost no sound could escape her huge, high-ceilinged room. After living through the noises of Jalasso’s first year of tennis obsession at age three, her mother had made sure of that, having insulation put in all around it to keep the repetitive “pock” sounds from invading the rest of the house at all hours. “Ixnay on the amplay,” she said. “You mean ‘the racquet that needs to be restrung.’”

He nodded. “Yes, the racquet,” he said in a monotone.

“That needs to be restrung.”

“That needs to be restrung,” he repeated.

Jalasso nodded happily, her dark, bobbed hair bouncing with the effort. “The racquet that needs to be restrung,” she prompted.

Tommy knew better than to continue. She’d have her way, or he’d never get back on that invitation list. After the amazing party favors of the past two years, he didn’t dare miss one of Jalasso’s parties. And the rumors had already started that there would be drawings for courtside seats at Flushing Meadow. “Can we just get your racquet that needs to be restrung and go?” he asked.

Jalasso bounced once and spun on her heel. “Let me go pick out a bag and we’ll go,” she said.

[part three]

Part Two: The Racquet That Needs To Be Restrung

Jalasso couldn’t believe how obvious Tommy was when he came to sneak away with the lamp. She wanted him to do it right, and she had half a mind not to restore his name to the birthday party list because of his poor performance. It was only the effectiveness of the job that convinced her not to be too hasty. She could cut him from the list for some other trifle, but she’d never bribe another favor out of him if she went back on their deal. She’d just wait another week or so, then find something that he said so offensive that she’d have no choice but to drop him from the invitation list.

She had dumped the contents of her wastebasket into a cosmetics bag to keep the maids from finding the broken glass. Jalasso meant to get a trash bag, but she couldn’t find any and she didn’t want to raise suspicion by asking. Then she thought she might find a shopping bag, but those were all gone. Groceries were almost always brought to the house by delivery, so she couldn’t even find a simple brown bag. At least the cosmetics bag was just a giveaway item her mother got with some boutique purchase. Plus, it zipped, which kept it from spilling.

The lamp itself was a lot harder to figure out. She needed to hide both the lamp’s base and the tangle of metalwork that had once helped define the shape of the stained-glass lampshade. Jalasso experimented with the latticework of soft metal that had made up the shade, and she found she could bend it very easily. But there were still a lot of glass fragments stuck to it, so she worried that she might cut herself and then the cut would get infected and then she wouldn’t be able to hold her racquet right and something like that could very well cost you a match. Better not to risk it. And, really, that was mostly Tommy’s job, getting rid of the lamp. When he got there, he could bend the metalwork in order to make it fit.

She’d told Tommy to bring something to put the lamp base and shade in, because she was stumped. The base would stick out of most bags, and even if Tommy could mash it down, the shade was going to have a weird shape that would be hard to hide. What if she just threw them both out the window and Tommy maybe stood outside and caught them? But her room was four stories up. She’d seen Tommy try to return her own forehand, and she knew he wasn’t really that coordinated. Besides, somebody might see. But Tommy said he had an idea.

When the butler, Marble, announced Tommy at Jalasso’s bedroom door, he mentioned that young Mr. Penchant had arrived for their tennis date. Jalasso tried not to react, but she knew that if she realized she should try not to react, she probably already had reacted with the kind of annoyed look of surprise she always displayed when she heard something she hadn’t expected or didn’t like. But Marble didn’t care as long as he believed Jalasso’s current mischief wasn’t dangerous. Plus, Jalasso had to admit that nine times out of ten, that’s the reason any of her peers came to her room.

“But you didn’t even bring a racquet!” Jalasso complained once they were alone in her room. “That’s not believable. Tommy, please don’t get me in trouble. I’m serious.” Ever since Tommy agreed to come help her with the lamp, she’d been pacing her room, spinning her racquet in her hands, and nervously keeping balls aloft with gentle taps. She kept imagining her mother finding out about the lamp. She could almost hear the sound of her mother’s voice telling the tennis camp that, fine, they could keep her deposit. But no way was Jalasso Pei making an appearance that year at their facilities. She could see all the other girls lined up during the morning clinics, smiling and flirting with Johann Bjornbornssen. And stupid Amy with her stupid blonde pigtails grinning at him with her big stupid mouth and fat, fat lips. It had started to make Jalasso sick with anticipation.

“No one noticed,” Tommy said. “Besides, that’s how we’re taking everything out. In one of your tennis bags.”

Jalasso stopped for a moment as she took hold of the information. She could have done the same thing herself! The lamp was exactly the right size for one of her big shoulder bags. And if she bent it right, the shade would flatten out to be about the size of a racquet head. Of course, if one of the staff insisted as usual that they had to take the heavy items, then the lamp might have been discovered. They’d let Tommy take his own bag, however. Not to mention the fact that she wanted to avoid that cut to the hand that would threaten her game. That was a risk she preferred Tommy take. Still, one thing bothered Jalasso.

“So you’re just taking one of my bags?” she asked. “Do I get it back?”

Tommy frowned at her in disbelief. “Jalasso, you have about twenty tennis bags at least.”

She threw out her hands. Some people just didn’t get anything. “They’re all different,” she explained. “Different sizes and styles and pockets and stuff. And I have five different ones from five different years I’ve been to the Open. So those are mainly just for my collection.”

Tommy rolled his eyes as dramatically as a silent movie star. He shook his head. “Fine,” he said. “I’ll bring your bag back. Whatever one you can live without for a couple of days. Next time I come play you, I’ll bring it back.”

Jalasso shook her head. “And, what, leave your racquet?”

“I can borrow one of yours.”

She flinched as if someone had tried to strike her. “What? Be serious.”

Tommy made a noise of frustration. “Fine! I’ll leave mine. Or I’ll bring one with a head cover with a strap and stick it inside the bag. We’ll figure it out. Can we just get your busted lamp and go?”

Jalasso made a shushing motion at Tommy, although almost no sound could escape her huge, high-ceilinged room. After living through the noises of Jalasso’s first year of tennis obsession at age three, her mother had made sure of that, having insulation put in all around it to keep the repetitive “pock” sounds from invading the rest of the house at all hours. “Ixnay on the amplay,” she said. “You mean ‘the racquet that needs to be restrung.’”

He nodded. “Yes, the racquet,” he said in a monotone.

“That needs to be restrung.”

“That needs to be restrung,” he repeated.

Jalasso nodded happily, her dark, bobbed hair bouncing with the effort. “The racquet that needs to be restrung,” she prompted.

Tommy knew better than to continue. She’d have her way, or he’d never get back on that invitation list. After the amazing party favors of the past two years, he didn’t dare miss one of Jalasso’s parties. And the rumors had already started that there would be drawings for courtside seats at Flushing Meadow. “Can we just get your racquet that needs to be restrung and go?” he asked.

Jalasso bounced once and spun on her heel. “Let me go pick out a bag and we’ll go,” she said.

[part three]

Thursday, July 21, 2005

jalasso pei, part-time potential junior tennis champ

Part One: The Lamp!

She was so mad that she wanted to break something, so she did. The Tiffany lamp never had a chance. Jalasso delivered to it a solid two-handed backhand with her favorite tennis racquet and watched in awe and anger as the multicolored glass shards of the antique shade scattered across the room.

“Moron!” she screamed at the high-definition flatscreen television hanging on the wall. On it flashed the pensive face of a linesman under scrutiny for a challenged call on a serve. Jalasso’s favorite player, Johann Bjornbornssen, stood before the official, holding out his hands plaintively. The linesman tried not to react.

“Jalasso Adromeda Pei!” called the weary voice of her mother from down the hall. “What are you doing in there?”

Jalasso whirled around toward the closed door of her cavernous bedroom. She tossed the racquet guiltily onto the canopy bed in the far corner. “Nothing!” she called back, her face in a grimace as she awaited her fate. She’d been warned about the tennis-induced outbursts before, and she was afraid her mother might eventually follow through on her threat to cancel her summer tennis camp enrollment.

“Are you injuring the furniture?” her mother asked, but Jalasso could tell that she sounded no closer. She breathed a small sigh of relief. There was still a chance.

“It was just glass!” she shouted, hoping the way she said it might lead her mother to believe she’d merely dropped a tumbler of water, that she hadn’t attacked her mother’s precious furnishings. It seemed like less of a lie that way. Some future cross-examination might yet require it.

There was a pause. Then her mother called, “Just a glass?” She still sounded no closer.

“Yeeeaaahhhh?” Jalasso said uncertainly. The lie was getting deeper now. She needed to keep her head.

Her mother sighed. “Well, get someone to clean it up,” she said at last. “And be more careful. If you don’t watch out, I’m calling that tennis camp and having them cross you off their list.”

“Okay, I will,” Jalasso said. She repeated it to herself to try to set the information deep in her mind. “I will. I’ll be good. I will. I’ll be good. I will …”

She couldn’t afford to miss the camp. Not that she hadn’t been there before. For several years now she’d been going to it, and she was in the top of the rankings in the Girls 8 to 10 Group. She was looking to break into a higher group this year, to play the older girls who were getting taller and faster already. But that wasn’t even the most important part. The most important part was the man on the television, who was even as she glanced up preparing to return serve on a crucial second-set break point. Because that summer the camp’s special guest pro was going to be none other than Johann Bjornbornssen!

Jalasso leapt lightly at the thought. She loved Bjornbornssen with all the devotion she could muster. And when it came to things tennis, that devotion was considerable, at times obsessively single-minded. It was evident from the posters and clippings that covered most of one vast wall of Jalasso’s room. It was evident in her choice of wardrobe, the majority of which featured blouses, skirts, and dresses intended as tennis sportswear. It was evident from the dozen racquets hanging at the far end of the room, the display case full of tennis ribbons and trophies, the stray tennis balls that littered the floor. And it was evident from the floor itself: a green, playable surface painted with thick white lines measuring a space of 78 by 27 feet.

Jalasso settled herself in a bright yellow beanbag designed to resemble a tennis ball. She tried to forget the awful call that had gone against her beloved Johann and to focus on the game. After all, the match wasn’t over yet. And it wasn’t like it was a Grand Slam event. Not that every game wasn’t extremely important to her, but she had to keep these things in perspective if she was going to do a convincing job of being good. She allowed that maybe she’d been a little hasty getting so mad that she’d broken that stupid lamp.

The lamp! She already forgot about the lamp! She bounded out of her chair and went to inspect the damage. The base of the lamp still looked okay, although she could see that it showed some scratches. She could put it back and turn the damaged part toward the wall. But that would never work, because the shade was beyond repair. Jalasso had been practicing her serve all spring, and she knew she’d hit the lamp as hard as some of her better, faster serves of recent weeks. Even in the middle of her desperation to figure out how to cover up the destruction, she couldn’t help but feel a little proud. She’d pulverized some of that stained glass!

Jalasso heard a cheer from the television, and she whirled around in time to catch the replay of the point she’d missed. Good. It was for Bjornbornssen. Well, she was recording the game anyway. She’d go back and look at the highlights later. She looked around the room and fetched a notebook from the oversized pine desk where she did her schoolwork. Tearing the front and back covers off the notebook, she used the thick cardstock to sweep the spray of broken glass into a neat little pile, then began depositing the glass into a wastebasket.

In a few minutes, she’d gotten rid of the majority of the glass, but she wasn’t sure how to make sure it was all gone. Plus she needed to make sure the lamp and the glass were safely thrown away without raising suspicion. She couldn’t just dump it in the trash and be done with it. The maids wouldn’t want to get in trouble for breaking or stealing it, so they’d probably mention it if they saw any part of it. Jalasso needed someone to haul the lamp away and make sure it was never seen again.

She placed the wastebasket and the lamp inside her closet. Then, skipping over to grab her mobile phone, she settled again in her beanbag chair and watched the onscreen action with rapt attention for a few minutes. Bjornbornssen had held serve, but he didn’t seem aggressive enough in trying to break his opponent’s serve. He was holding back, she decided. Maybe he’d make this an endurance match, betting that his legendary fitness would give him an edge when the man on the other side of the net began to tire. It wasn’t a tactic he’d used much this year, but there was a time …

Oh, but she still needed to get this lamp thing settled. Jalasso looked away from the television screen to prevent being distracted by it again and scrolled through the hundred-something numbers stored in her phone. She found her accomplice’s name in the list and hit the “call” button.

“Hello?” asked the hesitant voice of Tommy Penchant after a few distant rings. Jalasso sat with her hand over her eyes, but she was peeking between her fingers as Bjornbornssen leapt high for an overhead smash, evening the score and going to deuce. She squealed involuntarily at the exciting turn of events.

“Hello?” Tommy asked again, this time with a touch of fear in his voice at the unexpected sound of Jalasso’s loud, high-pitched exclamation. “Jalasso? Is that you? Are you watching a game?”

She stopped peeking at the game and regained her composure. She’d been well trained in her phone manners. “Tommy, hello,” she said warmly. “It’s Jalasso Pei calling. How are you today?”

“What’s going on, Jalasso?” Tommy asked.

“Ah, well, since you ask, I’ve called to ask for your help with something. I have a favor to ask.”

“What?”

“I’d be deeply in debt to you, Tommy.”

“Yeah?” Tommy asked, sounding a little more interested and a little less irritated.

“I would,” Jalasso said. “Birthday-party in debt.”

Jalasso’s birthday parties were known to be the best and the biggest and the most fun birthday parties in three states. Tommy had been both on and off the guest list multiple times over the past several months, depending on how recently he had either pleased or displeased the guest of honor. “Keep talking,” he said, as she knew he would. Jalasso smiled and allowed herself a glance at the television. Bjornbornssen had the advantage!

[part two]

She was so mad that she wanted to break something, so she did. The Tiffany lamp never had a chance. Jalasso delivered to it a solid two-handed backhand with her favorite tennis racquet and watched in awe and anger as the multicolored glass shards of the antique shade scattered across the room.

“Moron!” she screamed at the high-definition flatscreen television hanging on the wall. On it flashed the pensive face of a linesman under scrutiny for a challenged call on a serve. Jalasso’s favorite player, Johann Bjornbornssen, stood before the official, holding out his hands plaintively. The linesman tried not to react.

“Jalasso Adromeda Pei!” called the weary voice of her mother from down the hall. “What are you doing in there?”

Jalasso whirled around toward the closed door of her cavernous bedroom. She tossed the racquet guiltily onto the canopy bed in the far corner. “Nothing!” she called back, her face in a grimace as she awaited her fate. She’d been warned about the tennis-induced outbursts before, and she was afraid her mother might eventually follow through on her threat to cancel her summer tennis camp enrollment.

“Are you injuring the furniture?” her mother asked, but Jalasso could tell that she sounded no closer. She breathed a small sigh of relief. There was still a chance.

“It was just glass!” she shouted, hoping the way she said it might lead her mother to believe she’d merely dropped a tumbler of water, that she hadn’t attacked her mother’s precious furnishings. It seemed like less of a lie that way. Some future cross-examination might yet require it.

There was a pause. Then her mother called, “Just a glass?” She still sounded no closer.

“Yeeeaaahhhh?” Jalasso said uncertainly. The lie was getting deeper now. She needed to keep her head.

Her mother sighed. “Well, get someone to clean it up,” she said at last. “And be more careful. If you don’t watch out, I’m calling that tennis camp and having them cross you off their list.”

“Okay, I will,” Jalasso said. She repeated it to herself to try to set the information deep in her mind. “I will. I’ll be good. I will. I’ll be good. I will …”

She couldn’t afford to miss the camp. Not that she hadn’t been there before. For several years now she’d been going to it, and she was in the top of the rankings in the Girls 8 to 10 Group. She was looking to break into a higher group this year, to play the older girls who were getting taller and faster already. But that wasn’t even the most important part. The most important part was the man on the television, who was even as she glanced up preparing to return serve on a crucial second-set break point. Because that summer the camp’s special guest pro was going to be none other than Johann Bjornbornssen!

Jalasso leapt lightly at the thought. She loved Bjornbornssen with all the devotion she could muster. And when it came to things tennis, that devotion was considerable, at times obsessively single-minded. It was evident from the posters and clippings that covered most of one vast wall of Jalasso’s room. It was evident in her choice of wardrobe, the majority of which featured blouses, skirts, and dresses intended as tennis sportswear. It was evident from the dozen racquets hanging at the far end of the room, the display case full of tennis ribbons and trophies, the stray tennis balls that littered the floor. And it was evident from the floor itself: a green, playable surface painted with thick white lines measuring a space of 78 by 27 feet.

Jalasso settled herself in a bright yellow beanbag designed to resemble a tennis ball. She tried to forget the awful call that had gone against her beloved Johann and to focus on the game. After all, the match wasn’t over yet. And it wasn’t like it was a Grand Slam event. Not that every game wasn’t extremely important to her, but she had to keep these things in perspective if she was going to do a convincing job of being good. She allowed that maybe she’d been a little hasty getting so mad that she’d broken that stupid lamp.